Ara mateix a Calais, a França, hi ha nens donant voltes sobre una acolorida noria plena de neons, alcen els braços (mira, sense mans!) mentre recorren a gran velocitat, i sobre un vagó amb forma de granota, un circuit infinit de mini-muntanyes. Fa olor salada de marisc acabat de fer, que ve de restaurants plens de fina porcellana, d'aquella blanca i daurada. Els carrers estan cuidats, adornats amb vestits d'estiu, gossets, gorres, fanals clàssics, i tothom passeja tranquil·lament entre una fresca brisa marina. Hi ha una torre amb un rellotge engalanat amb tot tipus de braçalets daurats i uns jardins públics amb uns arbustos perfectament retallats i en forma de terròs de sucre gegant.

Hi ha les restes d'una batalla que ha quedat quasi oblidada; hi ha búnquers de ciment, unes monumentals estructures arquejades que formen una línia de punts sobre la platja, que s'alcen orgullosos d'haver sobreviscut a tants soldats a qui pretenien protegir durant la Segona Guerra Mundial. Arsenals grisos que es cauen a trossos, que son testimoni de la continua i insaciable set de guerra que té l'home.

I hi ha un tros de 4km de platja que conté més de 7,000 persones, les quals han viatjat grans distàncies per residir en un assentament il·legal anomenat "la jungla de Calais". França es nega a reconèixer a aquesta gent com a refugiats, de manera que entre el campament i els humans que hi viuen diuen, tot xiu-xiuejant, que són "il·legals". La paraula que millor descriu l'assentament seria "tuguri" o "favela"; la gent viu en estructures que van des de tendes de campanya, a barraques de fusta, fins a estructures més sofisticades fetes de metall rugosos i reutilitzat (tot i que ara la policia registra a tothom que entra i confisca qualsevol tipus de material de construcció o eines, per tal d'assegurar-se que ningú pugui crear o construir un espai per viure agradable). Hi ha poca aigua corrent, la gent fa servir

Polyklyns com a lavabos, hi ha una sensació general de fredor, humitat i fangositat fins i tot al pic de l'estiu.

A Calais existeixen dues realitats molt separades. Aquestes estan segregades per barreres físiques, i també per d'altres de menys físiques, com ve a ser el privilegi aleatori d'haver nascut amb un color de pell concret o en una àrea concreta del planeta. A causa d'aquesta divisió a molts de nosaltres, jo mateixa inclosa, se'ns fa fàcil distanciar-nos de la crisi dels refugiats. Els governs s'han assegurat que seguim fent vida normal a través d'eines com el mur d'aïllament de quatre metres d'alçada que recentment ha encarregat el President Hollande, i la prohibició a la cobertura mediàtica des de dins de molts camps de refugiats.

A causa del meu gran privilegi, vaig poder entrar com a visitant al campament de Calais. Vaig poder donar el meu passaport a la policia francesa que, armada fins a les dents, fan guàrdia davant de cada entrada, i després d'haver escanejat i revisat el meu passaport, vaig poder entrar lliurement. I encara més, també en vaig poder sortir quan em va venir de gust, cosa de no és el cas de la gent que hi viu.

I ara ve això “d'ajudar” i les complicacions que comporta.

He fet de "voluntària" moltes vegades, a molts llocs arreu del món. El que he vist i après és molt, i alhora molt divers, i algunes de les coses que he entès ressonen més que d'altres.

La idea de la sostenibilitat és un dels conceptes més importants que he après durant tots aquests anys de voluntariats. És sostenible aquest projecte? Si jo no hi fos, podria existir sense mi? Si la resposta és no, vol dir que estem fent alguna cosa malament. L'objectiu és mai no crear més dependència, perquè la dependència engendra jerarquia. En canvi, la idea final sempre hauria de ser "com aconseguir deixar d'aquesta feina", creant independència i un sistema on no hi siguis en absolut necessari.

Durant el temps que vaig passar a Calais em vaig recordar d'aquest concepte, ja que Calais bàsicament no podria funcionar sense totes les ONG que hi ha dins. Quan vaig entrar al camp amb la meva armilla blanca de voluntària, no vaig poder evitar adonar-me'n de la jerarquia que es creava. Jo sóc voluntari, tu refugiat. Mentre intercanviàvem tiquets per pantalons, camises, roba interior, sabó, paelles, el que sigui... el contenidor on es guarden les coses per distribuir calia que estigués vigilat per un voluntari. La gent que controla aquests productes, els qui els estan "regalant" tot això, són voluntaris (quasi tots blancs). El camp de Calais fa 20 anys que existeix, a cas la gent ja establera i que viu al camp no són capaços de crear i mantenir aquest tipus de distribució? Seria una imprudència ignorar aquesta dinàmica de "voluntaris" i "necessitats", ja que és crucial per tal d'entendre tant aquesta situació específica com el conjunt de la situació en general.

Ignorar la "crisi dels refugiats" ja no és una opció viable, ja que és un problema global; independentment de qui siguis, d'on visquis, del teu estatus econòmic, de si t'interessa o on la política, etc. La recerca sobre el escalfament global estima que l'any 2050 podria haver-hi uns 150 milions de

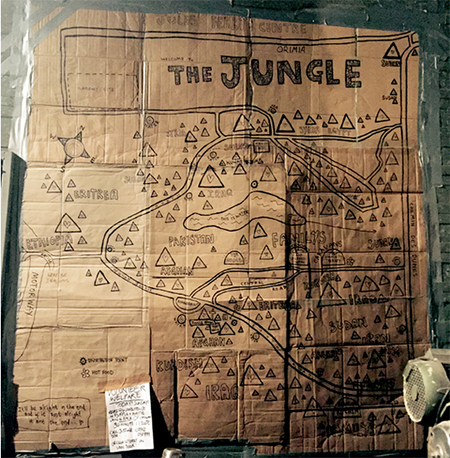

"refugiats pel clima". El mateix camp de Calais s'organitza en barris per països (hi ha una part afganesa, una sudanesa, etc.) i es pot llegir com un mapa literal dels llocs que els EUA i la UE han bombardejat. Aquestes guerres polítiques encara duren, i la quantitat de gent que ja no té un lloc on viure i han estat forçats a traslladar-se radicalment només fa que créixer. Calais rep unes 100 persones noves cada dia.

Potser el terme refugiat també dificulta la nostra capacitat per a empatitzar. De fet, la gent que vaig conèixer a Calais parlaven diversos idiomes, eren metges, advocats, adolescents impertinents, ballarins, artistes, poetes, jugadors de futbol, simples i complexos individus. A la tarda anava al camp a ensenyar i donar classes d'anglès i l'amabilitat dels meus alumnes em va colpejar tan fort que encara avui la sento. En dues ocasions diferents, durant dues classes llarguíssimes que vam fer, hi va haver alumnes que van marxar un moment per tornar amb un plat de menjar que havien anat a buscar per a mi. Tothom va deixar de fer el que estava fent i em van exigir que fes una pausa, mengés, begués, abans de tornar a la lliçó sobre objectes directes. Aquestes persones són humans, són exactament igual que nosaltres, igual que els nostres amics i la nostra família. Excepte que ells estan lluitant contra unes adversitats que nosaltres mai experimentarem.

Separar-nos de la població de refugiats, de fet, no serveix a ningú. Cal que ens exigim a nosaltres mateixos i als nostres governs llibertat total per a la integració. La història ha demostrat una vegada i una altra que quan a algú li lleves tots els drets, totes les llibertats i tota humanitat, aquell algú farà tot allò que necessiti fer per tal de sobreviure. Sovint aquestes accions no són maques i poden anar en detriment de tots aquells que els envolten.

Els habitants de Calais són quasi tots homes, perquè moltes dones i nens i nenes no poden fer un viatge tan arduós. Fer milers de quilòmetres a peu, pagant milers d'euros a traficants, nedant, agafant una petita barca de plàstic per travessar el mar, amagant-se sota d'autobusos, escapant-se corrents de la policia, dormint pel carrer – aquestes condicions fan que sigui quasi impossible viatjar en grup. Quan vaig presentar la meva família i a mi mateixa a una de les persones d'allà, aquest immediatament va esclatar en plors, li faltava l'aire, i va haver d'excusar-se i marxar. Quan es va calmar va tornar per disculpar-se i ens va explicar que la idea d'una família unida és quelcom que ell mai tindrà el privilegi de saber què és.

Potser pensareu que uns 7.000 homes, que molt sovint no es poden comunicar entre si a causa de no parlar el mateix idioma, i que es troben enmig de la pitjor, i la més indigna situació de la seva vida, podria donar com a resultat una atmosfera lleugerament tensa. No dubto ni un moment a l'hora de dir que la població francesa de Calais, qui es nega a donar cap tipus d'ajuda als nouvinguts, té molta sort que la gent de dins del campament siguin molt més humans que ells, o la ciutat potser seria cremada i reduïda a cendres.

I aquest és només un campament de centenars i centenars més que hi ha per Europa. Per què estem esperant que aquesta situació arribi al límit?

![]()

Cal que repensem del tot la manera que tenim de concebre aquesta "crisi de refugiats". Un petit però increïble exemple, que és un dels meus records preferits dels dies que vaig passar a l'assentament. El meu brillant company va proposar a alguns dels meus alumnes d'anglès que després de la classe ells es convertissin en els professos i li ensenyessin àrab. El resultat va ser una classe de quasi tres hores d'exuberància, malgrat la cara de cremada de gamba que tenia el susdit company. Un intercanvi igual, el reconeixement que tothom té quelcom igual de valuós per a oferir.

Un bon amic meu té una granja a Ocata que visito amb regularitat; un dia de treball a la granja a canvi d'una setmana de verdures. Mentre que ell és dels EEUU i el seu soci de Catalunya, l'altra gent que treballa a la granja són tot persones que han vingut a Catalunya a causa de les condicions de vida insostenibles que hi ha als seus països. La granja no podria funcionar sense aquesta gent, i a canvi Catalunya els ha obsequiat amb la ciutadania. Aquests treballadors tenen contractes de feina, reben classes de català i castellà, i tenen l'amistat assegurada dels seus "jefes". Tothom que treballa a la granja té la mateixa habilitat per treballar, viure i menjar. He tingut la sort de formar part de moltes celebracions i sopars en grup a la granja, àpats decorats amb taules plenes de menjar tan divers i deliciós com la gent que hi ha al voltant.

Aquests dos petits exemples són maneres d'il·lustrar com és possible abordar la qüestió de la reubicació de forma igualitària. I mentre entenc la necessitat urgent de proveir a la gent que està en una situació límit amb coses de primera necessitat, no crec que a la llarga aquestes estructures com els voluntariats portin a un futur sostenible per a aquells qui involucra.

Al campament de Calais, l'única ajuda que França ha aportat ha estat enderrocar tota una part de l'assentament per a instal·lar-hi una zona vallada amb contenidors de vaixells perquè la gent hi visqui. La gent que entra té l'opció de renunciar a la seva identificació, i a la possibilitat de ser reunits de nou amb les seves famílies a Anglaterra, a canvi de ser empaquetats en aquests contenidors metàl·lics. Fins i tot aquells qui viuen en contenidors a Calais no tenen la ciutadania francesa assegurada. Per algú amb família que va sobreviure als camps de concentració nazis, aquests contenidors són inquietantment reminiscents dels vagons amb els quals s'enduien la gent durant l'Holocaust.

Hauríem d'estar exigint que la Unió Europea i els nostres governs busquin i acceptin ciutadans nous de manera activa. Obrir la frontera del sud, amb Àfrica, voldria dir que la gent tindria accés directe a Espanya i Catalunya, en lloc d'haver d'arriscar la vida i estar patint de manera terrible. Cal que insistim a les agències de notícies perquè informin de forma regular i honesta sobre què és el que realment està passant a dins dels camps de refugiats. Cal que ens assegurem que els nous membres d'aquesta comunitat tinguin tot allò que calgui per a prosperar, integrar-se i sentir-se acceptats. Cal que escoltem i aprofitem els coneixements i els recursos que aquests nous ciutadans poden oferir-nos.

I encara més important, cal que ens adrecem als bel·licosos a qui els nostres impostos donen suport, i a l'impacte mediambiental que fa que aquesta gent hagi de fugir de casa seva. Cada persona amb qui vaig parlar al campament no desitjava res més que poder tornar al seu país d'origen, si tan sols hi fos habitable.

La situació a Calais us hauria de semblar deplorable, ja que les condicions són del tot aterridores. Però més aviat del que ens pensem no caldrà que anem a un campament de refugiats a Calais o a Grècia, perquè la crisi estarà al replà de casa (sigui on sigui aquest replà). Pas a pas s'acosten amb fermesa, però aquesta pressa no ens hauria de distreure de centrar-nos en la sostenibilitat més immediata. Quan els murs i les lleis de les regulacions més inhumanes piquin a la porta, a quin cantó de la història seràs tu?

![]()

---------- TEXT ORIGINAL EN ANGLÈS ---------

POSTCARDS FROM CALAIS REFUGEE CAMP AND THE SHORTCOMINGS OF VOLUNTEERING

Right now in Calais, France there are children twirling around a glowing neon ferris wheel, they are raising both arms (look no hands!) as they speed around an endless loop of mini-mountains in little cars shaped like frogs. There is the briny smell of freshly cooked seafood coming from restaurants filled with fine white and gold china. Well-maintained streets adorned with sundresses, small dogs, baseball caps, gauzy street lamps; all of which are casually strolling amongst a chilly sea breeze. There is a clocktower that wears all sorts of golden bracelets and public gardens with shrubbery shaped like perfect, giant green sugar cubes.

There are the remains of a battle almost forgotten; giant arched cement bunkers dotted along the beachline standing proudly, outliving so many of the soldiers it aimed to protect during World War II. Crumbling grey arsenals which bear witness to human’s continual, unquenchable thirst for war.

And there is a 4km stretch of beach that contains over 7,000 people, all of whom have traveled a great distance to reside in an illegal settlement termed “the Calais Jungle”. France refuses to acknowledge the people as refugees, so the encampment and humans inside are referred to in whispers as ‘illegals’. The settlement can best be described as a ‘slum’ or ‘favella’; people reside in structures that range from camping tents, to simple wooden shacks, to more sophisticated repurposed corrugated metal structures (although police now check everyone who enters and confiscates any building materials or tools as a means to insure no one is able to create too nice a living space). There is little running water and electricity, people use plastic porter potties as bathrooms, and there is a general cold, damp, muddy feeling even during the peak of summer.

In Calais there exists two very separate realities. They are segregated by physical barriers and less physical barriers like the random privilege of being born to a certain skin color or area of the planet. Because of this partition it’s easy for many of us, myself included, to remove ourselves from the refugee crisis. Governments have ensured we go about our normal living using tools like President Hollande’s newly commissioned 4 meter high, soundproof wall and banning press coverage inside many refugee camps.

Because of my own extreme privilege I was able to be a visitor at the Calais camp. I could offer up my passport to the heavily armed French police standing guard outside every entrance and after scanning and checking my passport, I would pass freely. More significantly, I could also leave as I pleased, which in many ways is not the case for the people living inside.

And here’s the part about ‘helping’ that gets quite tricky.

I have played the role of ‘volunteer’ many times, in many places around the world. What I’ve learned and seen has been vast and vastly different, some understandings more resounding than others.

The idea of ‘sustainability’ has been one of the most important concepts I’ve learned in my years of volunteering. Is this project sustainable? If I were not present, could it exist without me? If the answer is no, we’re doing something wrong. The point is never to create more dependence, because dependance breeds hierarchy. Instead, the end vision should always be ‘working yourself out of a job’, creating independence and a system where you’re absolutely not necessary.

I am reminded of this concept in my time at Calais, which simply could not function without all the NGO’s inside. When I walked into the camp wearing my white volunteer vest, I couldn’t help but notice the hierarchy created. I am a volunteer, you are a refugee. As we exchange tickets for pants, shirts, underwear, soap, pans, you name it, the storage container for distribution must be guarded by volunteers. The people who are in control of these items, who are ‘gifting’ them to people, are volunteers (almost only white). Calais camp has existed for 20 years, aren’t the established people who live inside the settlement also capable of creating and maintaining this type of distribution? It would be unwise to ignore this ‘volunteer’ and ‘those in need’ dynamic because it’s crucial to understanding this specific situation and the larger one at whole.

Ignoring the ‘refugee crisis’ is no longer a viable option because it is a global issue; no matter who you are, where you live, if you’re political or nonpolitical, your economic standing, etc. Global warming research estimates that in the year 2050 there could be as many as 150 million

‘climate refugees’.The Calais camp itself is organized into neighborhoods of countries (there’s an Afghan section, a Sudanese section, etc) and reads like a literal map of US and EU bombing sites. These political wars are ongoing, and the people who no longer have a place to live and are forced to radically relocate are only growing. Calais receives about 100 new people every single day.

Perhaps the general term ‘refugees’ also hinders our ability to sympathize. In fact, the people I met at Calais spoke multiple languages, were doctors, lawyers, bratty teenagers, dancers, artists, poets, footballers, complex, simple, individuals. During the evenings I went into the camp to teach and tutor English and was hit so forcefully by the kindness of my students, I carry the blows with me today. On two separate occasions, during two extra long classes I had students leave and return with food for me. The entire class stopped and demanded I take a break, eat and drink before resuming our lesson about direct objects. These people are humans, they are exactly the same as us and all of our friends and our families. Except that they happen to be struggling through profound hardships we will never know.

Separating ourselves from the refugee population in fact serves no one. We must require from ourselves and our government full and total liberty towards integration. History proves time and time again that when you remove all rights, liberties, and common humanities from someone, they will do whatever they need to survive. Many times these actions are not pretty and can be to the detriment of all those around them.

The inhabitants of the Calais settlement are almost only men, because many women and children can not make such an arduous journey. Walking thousands of miles, paying thousands of euros to smugglers, swimming, taking tiny plastic rafts across the sea, hiding beneath busses, running from police, sleeping on the streets-- these conditions make it almost impossible to travel in a group. When I introduced myself and my family to one of the people there, he immediately erupted into tears, began tightly gasping for air, and had to excuse himself. Once calm, he returned to apologize and explained the idea of a family together is something he will never have the privilege to know.

You might imagine that about 7,000 men, who many times can not communicate with one another due to lack of language commonality, are in the hardest, least dignified trial of their lives could prove for a slightly tense atmosphere. I do not hesitate to say that the French people of Calais, who refuse to assist the newly settled people in any way, are so lucky that the people inside the camp are far more humane than themselves, or perhaps the city would be burned to a crisp.

And this is only one small camp out of hundreds and hundreds in Europe. Why are we waiting for this situation to come to a boiling point?

We need to totally change our way of thinking about this ‘refugee crisis’. A small but incredible example is one of my favorite memories from my time at the settlement. My brilliant partner proposed to some of my English students that after class they instead become the teachers and teach him Arabic. The result was an almost 3 hour class of all around exuberance, despite the lobster-like sunburn on the face of said partner. An equal exchange, the acknowledgement that everyone has something equally valuable to offer.

A dear friend of mine has a farm in Ocata that I regularly visit; a day of farm work for a week’s worth of veggies. While he is from the USA and his business partner is from Catalunya, the other people who work on the farm are all people who have come to Catalunya because of unlivable conditions in their own countries. The farm could not function without these people and in return Catalunya was gifted with their citizenship, these workers receive work contracts, Catalan and Spanish lessons, and infallible friendship from their employers. Everyone who works together on the farm has the equal ability to work, live, eat. I have had the luck to be a part of many holiday and group farm dinners decorated with tables full of food that is as diverse and delicious as the people sitting around them.

These are two very small illustrations of ways it’s possible to approach relocating on an equal basis. And while I understand the urgent necessity to provide people-on-the-brink with human basics, I do not think ultimately structures like volunteering will lead to a sustainable future for anyone involved.

In the Calais camp, the only visible aid France has provided is by tearing down a section of the settlement and installing a fenced off area of shipping containers for people to be housed. People coming in are given the option to give up their identification and the chance to be reunited with their families in England in order to be packed into metal shipping containers. Even those living in the containers of Calais are not ensured French citizenship. As someone with family who survived the Nazi concentration camps, these are eerily reminiscent of the boxcars used to ship people during the Holocaust.

Instead, we need to be demanding that the EU and our own governments are actively seeking and accepting new citizens. Opening up the southern border with Africa would mean people would have a direct entrance to Spain and Catalunya, rather than risking their lives and suffering tremendously. We need to insist news agencies regularly report and give honest answers to what is actually happening inside these refugee camps. Make sure the newest members of this community have everything they need to thrive, integrate, and feel welcomed. Listen to and take advantage of the knowledge and resources these new citizens have to offer.

And most importantly we need to address the warmongering our tax dollars support and the environmental impact that drives people from their homes. Every single person I talked to at the camp wanted nothing more than to return to their home country, if only it was liveable.

The situation in Calais should seem deplorable to you, as the conditions are absolutely haunting. But sooner than we can imagine, it will not be necessary to travel to a refugee camp in Calais or Greece, because the crisis will be at our doorsteps (wherever your ‘doorstep’ might be). The footsteps are steadily approaching, but this rush should not distract us from focusing on immediate sustainability. When the walls and laws and inhuman regulations come knocking, on which side of history will you be?

Fotografia de portada: Eduard J. Montoya Text: Shaina Joy Machlus Traductora: Núria Curran Correcció: Pendent